How to Write Songs in Minor Keys

As musicians, we are always looking for new ideas we can incorporate into our playing and compositions. One thing I like to do when I come across a new idea, is to figure out how to conceptually reduce it into a set of easy and simple to apply rules. Being a metal musician, I’ve been interested in writing songs in minor keys.

So when I started learning about minor keys… that’s exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to create some easy to apply rules that make my life easier and makes my music more interesting.

If you’ve looked into music theory, you might know that there are several different types of minor scale:

- Natural Minor

- Harmonic Minor

- Melodic Minor

Which is pretty cool… but where does that leave us for song writing? And especially for writing songs in minor keys?

You might have seen how to harmonise scales with triads (or, how to make chords from scales). So when I saw these minor scales and I started thinking about how to use them to write music… I started looking into building chords from the scales

Quickly, I found myself wondering:

“Can I only write in one particular minor scale at a time?”

“If I want to move between scales, do I have to learn complex modulations?”

It turns out, I was completely overthinking the entire process.

When it comes to writing songs in minor keys, we can use chords from ANY of those three minor scales. The chords in those three scales are interchangeable and together, they make up a minor key.

If you ever wanted to write neoclassical metal… well that is the secret. Or pop songs. Or classical music. Whatever. It works.

Which leads us to the next question:

“Ok that’s cool, but there is a crap load of chords to work out there.”

Yes, there is. It would be a great exercise for you to go through them and work them all out. But as this is a journal for my own notes, I’m going to put down the ‘answers’:

| Natural Minor: | i | iio | bIII | iv | v | bVI | bVII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Minor: | i | iio | bIII+ | iv | V(7) | bVI | viio |

| Melodic Minor: | i | ii | bIII+ | IV(7) | V(7) | vio | viio |

Key:

Lower case numeral = minor chord

Upper case numeral = major chord

o = diminished chord

+ = augmented chord

(7) = Can also be a dominant 7 chord if you want

This table is a good starting point for showing us what options we have available for composing.

I like to whittle this table down to the chords that are easiest to use, and to also omit the names of the scales.

When I’m writing music, I don’t want to be thinking “this is this scale and this is that scale”, I want a fast list of rules I can apply.

Removing duplications:

| i | iio | bIII | iv | v | bVI | bVII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ii | bIII+ | IV(7) | V(7) | vio | viio |

This is pretty cool – we’ve now reduced a complex piece of theory into a small table of chords we can use. It is also easier to memorise.

I’m not saying that you don’t need to bother learning how to spot which scales these chords come from. You should learn that, especially if you want to solo over the top of a progression that has been written this way. However, purely for the purposes of writing new riffs and coming up with musical ideas, you do not need to know which chord comes from which scale.

You just need to know what works.

As a side note, you should get used to writing progressions using the table, and then work out what scales to use to solo over it. This way, you will quickly learn how to spot which chords come which scales.

When it comes to minor keys, we have a couple of non-diatonic (chords out of the scale) that we can also use, that sound great:

Use of Non Diatonic Chords When Writing Songs in Minor Keys

Neapolitan Chord

Often when songwriting, the iio is problematic, by which I mean, it can sound crap. Fortunately, someone invented something called a Neapolitan chord, which is where we replace the 2nd chord in the key with a bII chord (a major chord whose root is on the b2 of the scale). We can update our table to the following:

| i | iio | bIII | iv | v | bVI | bVII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ii | bIII+ | IV(7) | V(7) | vio | viio | |

| bII |

It is a really cool chord, and you have almost certainly heard it being used extensively. This is a killer tool for writing songs in minor keys. It gives a bit of a phrygian sound to your music.

So for example, if we were in the key of A minor, the iio would be a Bdim chord. The Neapolitan chord would be Bb∆ (Bb major).

Picardy Third

Another neat trick when writing songs in minor keys, is something called a Picardy third. This is when the i chord is substituted with a I chord. It’s traditionally used at the end of pieces, but there is no reason you can’t slap it in the middle of a chord progression if you want to.

The music theory police will not come looking for you.

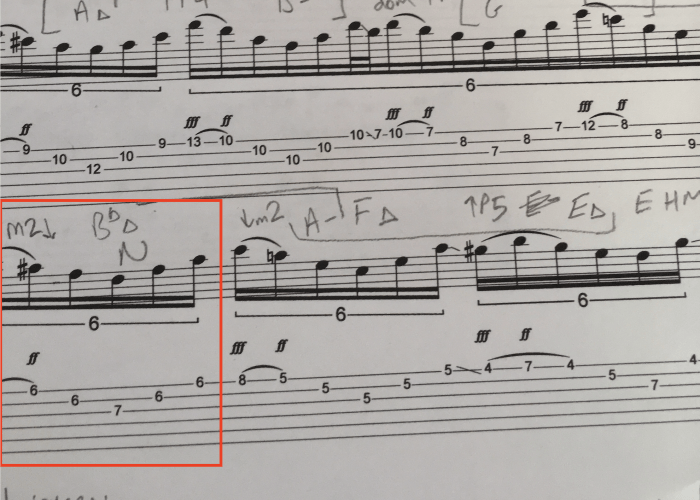

Seal put a Picardy Third in the verse sections of Kiss From a Rose… it seemed to work out well for him. Yngwie Malmsteen uses it all over the place (you can see a specific example in the arpeggio sequence in Liar.

Anyway, back to how this fits in with what we have worked out so far.

Adding the Picardy Third into our table:

| i | iio | bIII | iv | v | bVI | bVII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ii | bIII+ | IV(7) | V(7) | vio | viio |

| bII |

Example

As an example, let’s say we were writing in the key of A minor. Our table would look like this:

| A- | Bo | C∆ | D- | E- | F∆ | G∆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A∆ | B- | C+ | D∆ | E∆ | F#o | G#o |

| Bb∆ |

How can you apply this?

Literally anywhere you are writing songs in minor keys, or just a section of a song. You can use this to write chord progressions, to write riffs, or to write a cool sweep picking lick.

You can use this when you are analysing a piece, to help spot the function of non-diatonic chords.

Think of this table as a list of “things that musically work” together.

The best way to understand how to use this… is to have a go.

Write some chord progressions.

Write some arpeggio licks.

Have a go… and enjoy the results.